By Dan Steinbock

– Only countries that have won the battle against COVID-19 can fully reopen the economy. Others face difficult balancing acts. Southeast Asia is no exception.

I am writing this column in Pasay City, at the eye of Southeast Asia’s new pandemic surge. In late February, Pasay, a major destination hub of Metro Manila, reported the highest number of Covid-cases and second highest in the Philippines. Today, the city’s General Hospital is nearing full-bed capacity.

Pasay City is no longer alone. Today, the case numbers are still higher in other cities. The Philippines has hit its highest single-day increase one day after another and by March 20 the number of recorded daily COVID-19 cases surpassed 8,000.

As new variants and new spikes are spreading from Europe, United States and Brazil into lower-middle and low-income economies, emerging Southeast Asia is among the first world regions facing the new surge.

Considering China’s lessons in pandemic containment, reopening of the economy becomes viable only when COVID-19 is contained. Only a few countries in Southeast Asia fulfill the essential requirements for the full reopening.

Free Reports:

Get our Weekly Commitment of Traders Reports - See where the biggest traders (Hedge Funds and Commercial Hedgers) are positioned in the futures markets on a weekly basis.

Get our Weekly Commitment of Traders Reports - See where the biggest traders (Hedge Funds and Commercial Hedgers) are positioned in the futures markets on a weekly basis.

Sign Up for Our Stock Market Newsletter – Get updated on News, Charts & Rankings of Public Companies when you join our Stocks Newsletter

Sign Up for Our Stock Market Newsletter – Get updated on News, Charts & Rankings of Public Companies when you join our Stocks Newsletter

Spikes, variants in Southeast Asia

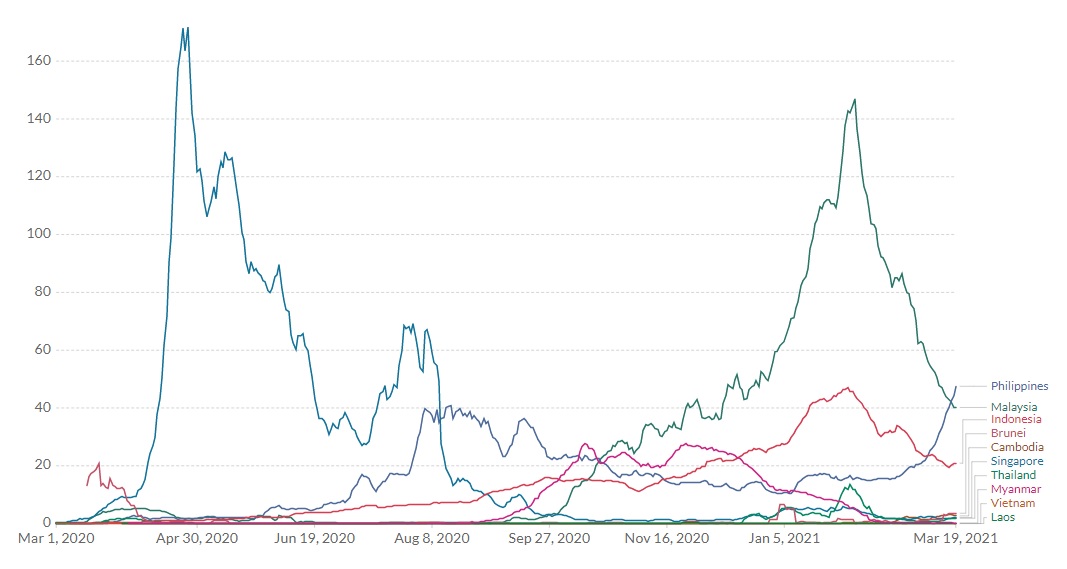

In Southeast Asia, the effectiveness of the pandemic containment can be measured by daily new confirmed infection cases per million people. In that view, the cases first soared in Singapore, which has been able to reduce the numbers dramatically. Excluding the high-income city state, the status quo is very different in emerging Southeast Asia (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Daily new confirmed COVID-19 cases per million people

Source: Johns Hopkins (7-day rolling average), DifferenceGroup (March 19, 2021)

Source: Johns Hopkins (7-day rolling average), DifferenceGroup (March 19, 2021)

From March to late fall 2020, Philippines had more per capita cases than the rest of the region. In the past four months or so, Malaysia has dominated the numbers. That changed after the first week of March, when cases in the Philippines surged across those in Indonesia and by mid-month across those in Malaysia.

The rest of Southeast Asia – including Thailand, Myanmar, and Vietnam – has experienced surges as well. But on per capita basis, none of them match those of the big three: Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia.

In addition to increased complacency and uneven enforcement, record case numbers in emerging Southeast Asia have been fueled by local transmissions and returning overseas workers and, most recently, by the new, more transmissible and harmful variants – as I projected first in late spring and again in late summer 2020.

Belated vaccination drives

The vaccination drives are picking up pace in the advanced economies, in part at the expense of the poorer countries. As some major economies have been hoarding vaccines, they have boosted excessive price levels and delayed deliveries elsewhere in the world.

Measured by COVID-19 vaccine doses per 100 people, the high-income Singapore is obviously in a class of its own with almost 14 doses daily per 100 persons. Excluding Singapore, the drives have started at varying pace across in Southeast Asia (Figure 2).

Figure 2 COVID-19 vaccine doses administered per 100 people

Source: Johns Hopkins (7-day rolling average), DifferenceGroup (March 19, 2021)

In the current status quo Indonesia is well ahead Malaysia and Cambodia, followed by Laos and Myanmar (until its ongoing turmoil). The four are tailed by the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam. But unlike Thailand and Vietnam, the Philippines has a very high number of cases.

Restricted mobility slows recovery

Targeted restrictions and lockdowns hold back recovery in Southeast Asia, especially in economies where caseloads remain high. A key role in these recoveries belongs to mobility. Restrictions seek to reduce interactions among people; mobility fosters those interactions. That’s why mobility is critical to the reopening of the economy, and why it also worsens pandemic risks.

Through the emerging Southeast Asia, all governments face a challenging balancing act. How to navigate between a premature reopening of the economy and excessive case numbers? The decisions will be most challenging in those countries that have suffered steepest contractions and highest case numbers.

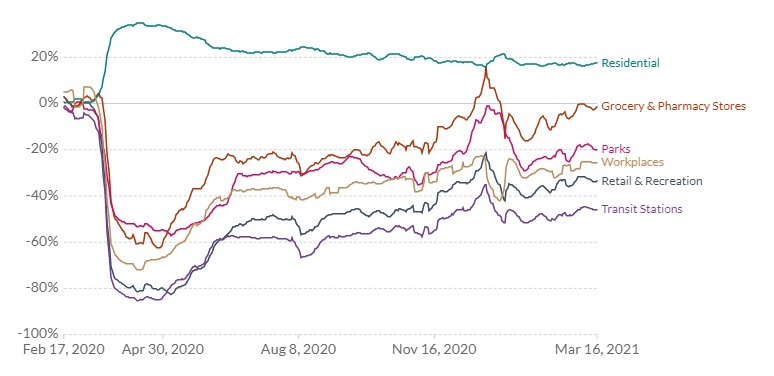

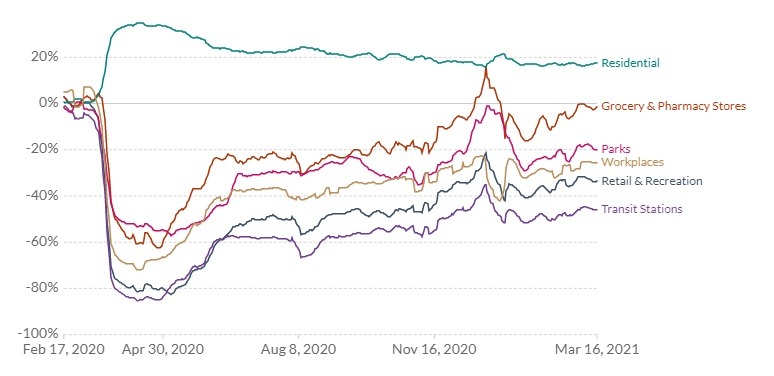

In terms of mobility, the Philippines, like much of Southeast Asia, took a severe hit in early 2020. As most people had to stay at home, the residential dimension surged to more than +30 percent. All critical mobility dimensions – groceries and pharmacies, parks and workplaces, retail and recreation, and particularly transit stations – suffered a decline of -50 to over -80 percent, each (Figure).

Figure 3 Change in visitors by category

Source: Google Mobility Trends, DifferenceGroup (March 16, 2021)

After the hard quarantine periods, all dimensions were recovering until Christmas holidays. Thereafter progress was halted. Currently, only groceries and pharmacies are operating close to the pre-pandemic normal. Parks and workplaces are about 20 to 25% below normal, and retail nearly 35% under capacity. Transit stations remain over 45% down.

Shrinking policy space, national unity vital

In late 2020, emerging Southeast Asia returned to its expansionary terrain. While policymakers must focus on reducing the short-term economic fallout, the pandemic will have long-lasting effects.

Those economies that are most reliant on tourism will suffer longer scarring than their peers. China’s early recovery will benefit countries that are broadening trade, investment and exchange ties with the mainland. Trade-dependent countries must cope with US-Sino tensions and Washington’s continued protectionism.

Interest rates have been reduced across Southeast Asia. In some they are already low (Thailand). In others, there is still policy room (Philippines). In still others, they remain relatively high (Indonesia, Vietnam). Rate hikes are not likely in 2021, as fiscal authorities and central bankers must ensure accommodative conditions.

In the past year, public debt levels have understandably climbed fast, yet remain 40% to 60% of GDP in Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Indonesia. It will take another 1-2 years until fiscal measures are rolled back.

External vulnerability, measured by reserves to gross external financing, is higher in Indonesia and Malaysia, which need additional buffers against volatility, but relatively lower in Philippines and Thailand.

In domestic politics, the pandemic crisis is testing all economies worldwide, including emerging Southeast Asia. In Thailand, longstanding polarization continues to simmer. In Myanmar, it has resulted in violent conflict. In Vietnam, friction is subdued officially. In Malaysia and Indonesia, political divides have intensified. In the Philippines, the 2016 meltdown of the Liberal Party has led some of its former leaders to questionable efforts to use the crisis to position for the 2022 election.

The human and economic costs of the pandemic crisis are far too high exploit in politics. As the past months have shown, those countries that can pull together in a time of crisis will recover faster, whereas those where political games predominate won’t. Southeast Asia will be no exception.

About the Author:

Dr. Dan Steinbock is an internationally recognized strategist of the multipolar world and the founder of Difference Group. He has served at the India, China and America Institute (USA), Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore). For more, see https://www.differencegroup.net

- Escalating conflict in the Middle East is forcing investors to shift funds to safe assets Apr 15, 2024

- US dollar exhibits remarkable strength amid global tensions Apr 15, 2024

- COT Metals Charts: Speculator bets led higher by Copper & Platinum Apr 13, 2024

- COT Bonds Charts: Speculator Bets led by 10-Year & 5-Year Bonds Apr 13, 2024

- COT Soft Commodities Charts: Speculator Bets led by Soybean Meal & Lean Hogs Apr 13, 2024

- COT Stock Market Charts: Weekly Speculator Bets led by VIX & S&P500-Mini Apr 13, 2024

- Singapore’s central bank (MAS) maintained its monetary policy settings. The ECB hinted at a rate cut soon Apr 12, 2024

- Australian dollar struggles amid robust US economic data Apr 12, 2024

- The Bank of Canada maintained its monetary policy settings. The FOMC minutes showed that policymakers will not be in a hurry to cut rates Apr 11, 2024

- US Dollar strengthens following high inflation data Apr 11, 2024